JUBA – Some 6.5 million people in South Sudan – more than half of the population – could be in acute food insecurity at the height of this hunger season (May-July), three United Nations agencies warned today.

Food insecurity has deteriorated to significant levels, with 20,000 people expected to suffer catastrophic levels of food insecurity between now and April in South Sudan.

The situation is particularly worrying in the areas hardest hit by the 2019 floods, where food security has deteriorated significantly since last June according to the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) report released today by the Government of South Sudan, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the World Food Programme (WFP).

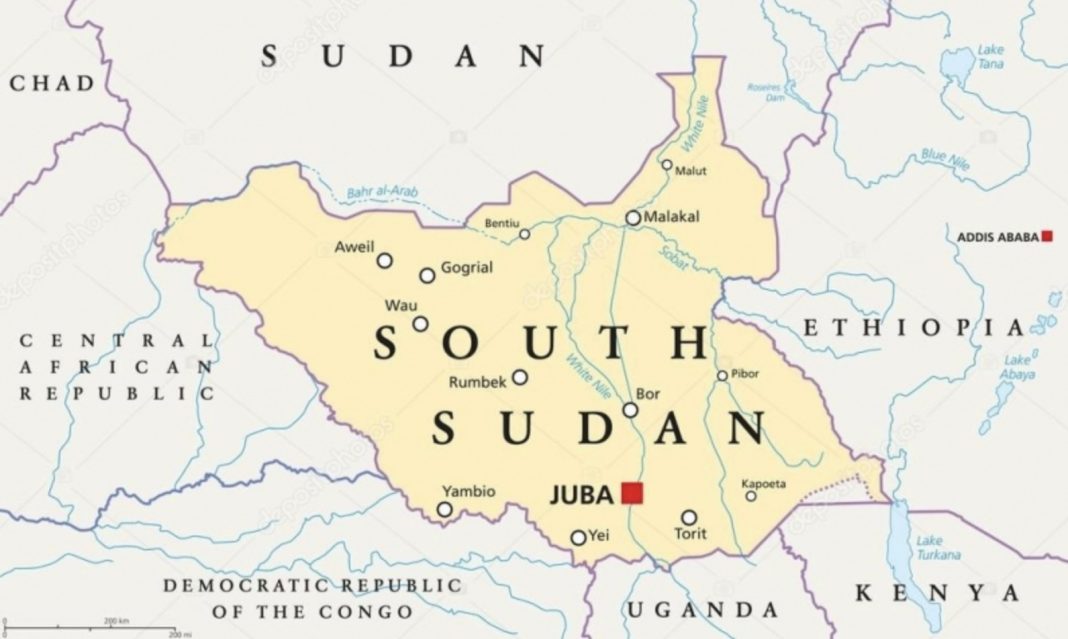

Particularly at risk are 20,000 people who from February through April will be suffering from the most extreme levels of hunger (“catastrophe” level of food insecurity or IPC 5) in Akobo, Duk and Ayod counties that were hit by heavy rains last year, and need urgent and sustained humanitarian support.

Hunger is projected to get progressively worse between now and July, mainly in Jonglei, Upper Nile, Warrap and Northern Bar el-Ghazal, with over 1.7 million people facing an “emergency” level of food insecurity (IPC Phase 4) due to the impacts of devastating floods and low levels of food production. Thirty-three counties will reach an “emergency” level of food insecurity during the hunger season, up from 15 in January

Overall, in January, 5.3 million South Sudanese were already struggling to feed themselves, or were in “crisis” or worse (IPC Phase 3 and above) levels of food insecurity.

“Despite some seasonal improvements in food production, the number of hungry people remains dangerously high, and keeps rising. On top of that, we are now faced with Desert Locusts swarms that could make this even worse. It is important that we maintain and scale up our support to the people of South Sudan so they can resume or improve their livelihoods and food production, and boost the government’s capacity to respond to the locust outbreak,” said Meshack Malo, FAO Representative in South Sudan.

Hunger is expected to deepen as of February due mainly to depleted food stocks and high food prices. Overall, the cumulative effects of flooding and related population displacement, localized insecurity, economic crisis, low crop production and prolonged years of asset depletion continue to keep people hungry.

“The food security situation is dire,” said Matthew Hollingworth, WFP’s Country Director in South Sudan. “Any kind of improvement which had been made was counter-balanced by the floods at the end of 2019, particularly for the hardest to reach communities. But this country is at a pivotal moment. This Saturday the government of national unity should be formed, and the gun silenced permanently. We will have to do more to meet the urgent needs of the most vulnerable as well as ensure communities across the country can recover so that in the future, they can withstand inevitable climatic and foods shocks.”

The report also notes that the country’s relative peace and stability have led to some improvements in the overall food security situation, with the upcoming lean season expected to be slightly less severe compared to last year’s, when 6.9 million people were in “crisis” or worse food insecurity.

For example, since the signing of the Revitalised Peace Agreement in September 2018, cereal production has increased by 10 percent, and a more stable environment allowed some of the farmers to resume their livelihoods, which combined with favorable rains has led to increased food production.

1.3 million children malnourished

The report also estimates that 1.3 million children will suffer from acute malnutrition in 2020.

Between 2019 and 2020, the prevalence of acute malnutrition among children slightly increased from 11.7 to 12.6 percent across the country, but the increase has been considerably higher in flood-affected counties – from 19.5 to 23.8 percent in Jonglei, and from 14 to 16.4 percent in Upper Nile. This can be attributed to less food being available, and high morbidity – mainly due to contaminated water and an upsurge in malaria from stagnant water.

“Over the years and with support from donors we have become good at treating malnutrition. With support from UNICEF and its partners, 92 per cent of all children suffering from severe acute malnutrition received assistance and more than nine out of ten recovered. Yet, these children shouldn’t be malnourished in the first place. Access to enough food, the right food, water, sanitation, hygiene, and health services are human rights and key to preventing malnutrition. There is a need for a paradigm shift with a multisectoral approach to malnutrition, ensuring we get just as good at prevention as we are at treatment,” said Mohamed Ag Ayoya, the UNICEF Representative in South Sudan.